Mrs Potatohead - Hannah McNeil on Character Development

So much of writing is interwoven. You can take individual aspects of a text - plotting, narration, voice, character, dialogue, action, metaphor, magic realism, and so on – but good writing is like the loose-weave woollen blankets that my grandmother used to make for the tourists. You could tease the fabric apart, separate each fibrous strand from the next, or you could stand back and wonder at the how the tartan rose out of the warp and weft; the yellow lines clear against the much stronger blues and greens.

Character is the basis of plot. Plot is the arc through which character changes. It is impossible to have one without the other. They are the warp and weft of the story.

When I first started writing, my characters were like soft clay on the wheel. I would press into them with a pallet knife to scar them with experience. I would fashion lips, ears, appropriate footwear, hoping the joins would not crack in the kiln. I wanted them to be self-supporting, clear in the reader’s mind.

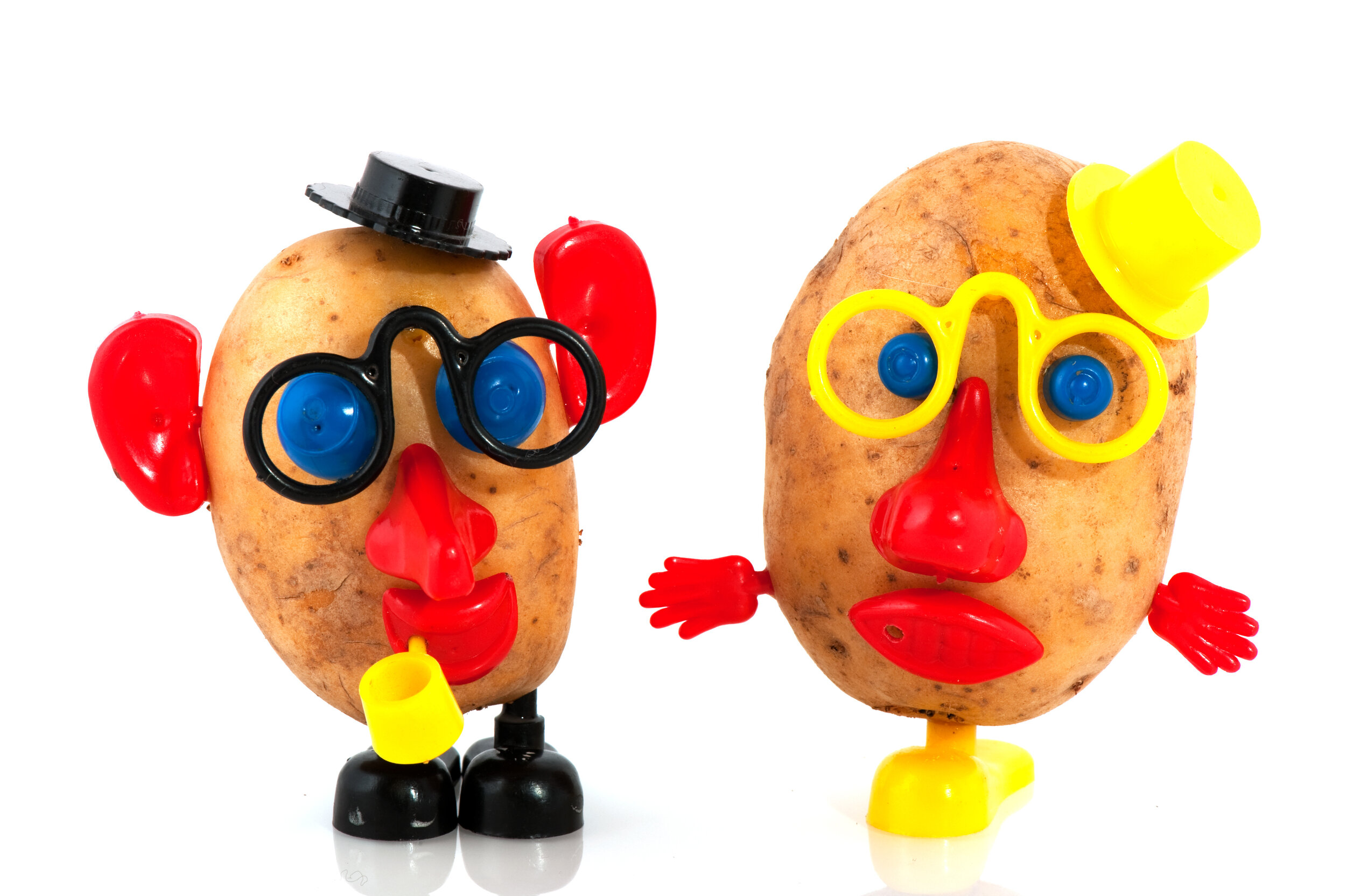

This is what I call the ‘hero approach’. The result is, of course, rather like the Mrs Potatohead toys, with attributes pinned to a neutral base; green eyes, a deep voice, fluent in Arabic from his time in the Negev (where he learned to shoot from horseback), and a scar down the outside of his right thigh that smarts whenever danger approaches.

But let’s not be too dismissive. Although this was a phase for me as a writer, it is also a stage each character has to survive in her birthing. There has to be backstory, and this has to be consistent with the character’s present. The reason James Bond is so desperate, and unsuccessful, at finding love is because he’s an orphan. The reason Luke Skywalker yearns to leave the desolate desert planet is because he has inherited his father’s genes.

There has to be consistency of height, weight, strength, perceptions of beauty. The writer Lee Child receives countless letters from fans of Jack Reacher, his dynamic creation, complaining that Tom Cruise is not right for the role. Reacher is six foot five; Cruise considerably less.

There also has to be psychological consistency. I use psychometric models – the Myers Briggs Type Indicator, Belbin’s Team Roles and so on - to shape how they behave. How does introversion manifest itself? Does it make them comfortable in their skin, or reclusive and shy? Do they write shopping lists? Do they doodle on the side of their notes? When they bend to pick up the crisp packet thrown by a youth in the city centre, do they tut and shake their heads, or march the miscreant to the nearest dustbin?

Now my plastic toys are becoming human. To flesh them out, I have a list of questions that help me understand them. What photos are by their bed? Who was their favourite teacher at school? Which newspaper do they read? What do they order when they go out for a meal with their father? What do they do about an injured hedgehog by the side of the road?

As I studied my craft, I discovered this approach has a name. It’s called Character Hotseating: shape the character in outline; shape the plot in outline; then interrogate the figurine with questions unrelated to the plot. How do you vote? What do you look for in a boyfriend? What would you wear to dinner at State House?

The questions don’t matter, but the answers do. They place the character in an active environment and force them to move through an imagined world; perhaps political, perhaps romantic, perhaps ceremonial. The character ceases to be a marionette at the beck and call of the writer, and starts to move of their own accord.

I read somewhere that characters need to surprise the writer. They need to have their own agenda, their own agency. If they don’t, they won’t surprise and delight the reader.

The writing guide books keep using the word ‘rotund,’ to describe a formed character. This does not mean fat, or even three dimensional. It means they act on their own behalf.

Thus, having matured from plastic toy to psychological independence, the next stage in character development (and the maturity of the writer) is to create decisive actors; people who makes choices the reader understands but does not necessarily support.

This is where plot comes in, the weft to the character’s warp. If the character behaves in a certain way, the plot must allow this to happen, or prevent it from doing so, thus creating implications later on. If the plot requires a character to choose between the green pill and the blue, they must have the ability to make the selection and the reader has to know it.

I find the relationship between plot and character fragile and iterative. At times, certainly in the first drafts of a novel, plot takes primacy and the character is yanked along. I am a character novelist, so eventually my peeps start to mould what happens and I find the plot lurching in a direction I had not anticipated. I tear up my plot notes and rewrite them. It is I who has to catch up.

So, as perhaps you can see, there is no simple answer to the question of character. They start as plastic toys, then become human, then expand into their skin, then choose their own ways of being. I feel them as I write. Their fingers tap the keyboard. Their eyes pick out the sheen of feathers on a bea eater, and their minds translate the words into German and back again. Their growth becomes my growth. In the evenings, I sit with them and play poker.

Some of them cheat.